Cider, as a beverage category, is simultaneously young and old. For centuries, it displayed distinct regional differences that were tied to local apple varieties and culture and an intimate connection to the seasons. Starting in the early 20th century, though, cider experienced a move to industrialization, with dominant mass-market producers using various forms of juice concentrate and/or apples picked young for cold storage then pressed year-round as needed. For the cider most readily available to consumers, the link to seasons and individual fruit character was broken.

Three recently published books shine a light on this profound difference in approach, coming down strongly on the side of complex flavor in the glass instead of streamlined production. Each book focuses on cidermakers who work seasonally, harvesting and pressing at peak ripeness, fermenting slowly (often with native yeasts), and aging as necessary—much the way a winemaker crafts a fine wine.

Three recently published books shine a light on this profound difference in approach, coming down strongly on the side of complex flavor in the glass instead of streamlined production. Each book focuses on cidermakers who work seasonally, harvesting and pressing at peak ripeness, fermenting slowly (often with native yeasts), and aging as necessary—much the way a winemaker crafts a fine wine.

First is drinks writer Jason Wilson’s book, Cider Revival: Dispatches from the Orchard, a very readable exploration of Wilson’s personal journey. He visits a handful of cidermakers, attends some of the most well-known cider gatherings, and, along the way, develops an appreciation for the fine seasonal ciders being made in New York state (the Finger Lakes region, in particular). Curiously, he skips cidermakers with a similar ethos in other parts of the country, electing instead to share his experiences at a number of hotel properties owned by the Trump Organization, which, while interesting, gives the book a slightly lopsided and somewhat incomplete feel. His zealous advocacy for the ciders he loves is, nonetheless, understandable.

Fine Cider: Understanding the World of Fine, Natural Cider, by Felix Nash, explores many regions of the cider world, though England is the main focus. Nash’s prose is lyrical as he writes of history, process, apples, and terroir. It’s easy to see oneself wandering through his landscapes, dancing with apple blossoms, or tasting leathery tannins as he sips a cider made of 27 mostly unidentified old varieties while sitting on a rocky beach on England’s southwestern coast. “[W]here cider is concerned, the natural variety and complexity of apples…are a source of charming fascination,” he writes. “[Y]ou are not limited to the predictability of a homogenized, seasonless cider, one that will never change, save when a focus group says it should.” His is a broadly applicable vision that calls for embracing local/seasonal products, wherever that may be.

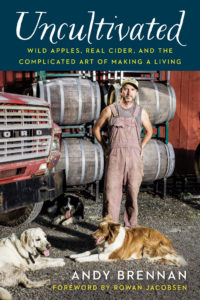

Cidermaker Andy Brennan, of Aaron Burr Cidery in Wurtsboro, N.Y., takes things a step further in his book Uncultivated: Wild Apples, Real Cider, and the Complicated Art of Making a Living. A believer in the use of feral apples, harvested in their place of origin (as the purest embodiment of place), and ciders made with the least intervention possible, Brennan’s book is a both a tale of his particular path and a philosophical exploration of progress and society, going beyond cider to muse on modern cultural attitudes as a whole. It’s a compelling and complicated book that left me thinking about the nature of trees, cidermaking as a form of art, and the industrialization of what we eat and drink. Yet the book ends on a note of hope—as do the others—that the cider category is turning away from the paradigm of mass manufacture and formulaic use of undistinguished juice and returning to its roots as a move toward a rich and complex future.

Cidermaker Andy Brennan, of Aaron Burr Cidery in Wurtsboro, N.Y., takes things a step further in his book Uncultivated: Wild Apples, Real Cider, and the Complicated Art of Making a Living. A believer in the use of feral apples, harvested in their place of origin (as the purest embodiment of place), and ciders made with the least intervention possible, Brennan’s book is a both a tale of his particular path and a philosophical exploration of progress and society, going beyond cider to muse on modern cultural attitudes as a whole. It’s a compelling and complicated book that left me thinking about the nature of trees, cidermaking as a form of art, and the industrialization of what we eat and drink. Yet the book ends on a note of hope—as do the others—that the cider category is turning away from the paradigm of mass manufacture and formulaic use of undistinguished juice and returning to its roots as a move toward a rich and complex future.