The act of making a beautiful beverage—the chosen techniques and ingredients, as well as the resulting style—reflect an artist’s hand. And when beverage producers come together to create a special release, the resulting product is, invariably, more than the sum of its parts.

“It’s a chance to work with great, like-minded people, and to rediscover the spirit of what brought us to this business in the first place.” — Jim Watkins, Sociable Cidery

Jim Watkins, cofounder and managing director of Sociable Cidery in Minneapolis, Minn., knows every possible problem that can crop up in a product collaboration, whether with another cidery, a brewery, or a distillery. First, of course, there are the reams of regulatory paperwork to negotiate, which are even more complicated when he and his collaborator produce different kinds of alcohol. Then there are the logistical issues, the production issues, and even the creative issues (trying to find common ground for a product that’s being made in conjunction with someone who might have a totally different perspective)—and Watkins could care less.

“There’s the blocking and tackling of running a light manufacturing business, and you have to do that,” he says. “Collaboration is the fun part. It’s a chance to work with great, like-minded people, and to rediscover the spirit of what brought us to this business in the first place.”

Such collaborations—when wineries, breweries, distilleries, and/or cideries work together to create a single product—have become a staple in the booze business. It’s more common among craft-sized producers, but larger companies have also gotten involved for the right cause. Those causes include fund-raisers, of which there were countless examples following last fall’s onslaught of natural disasters. But collaborations are also a key 21st century marketing tool, whether to publicize a region or AVA or to give producers a cross-promotional boost. And sometimes, as Watkins says, it’s just for fun.

“Collaboration beers are extremely hot right now,” confirms Julia Herz, craft beer program director for the 4,300-member Brewers Association, which represents craft breweries in the United States. “It’s a growing trend, because the craft business is extremely collaborative by nature.” Her analysis, say others interviewed for this story, applies elsewhere in the alcohol world as well.

Finding a reason

Talk to the people who do product collaborations, and it’s almost as if they don’t need a reason to do one. That’s apparently been the case since 2001, when two breweries that each made a Belgian-style beer named Salvation decided to collaborate instead of sue each other. This effort, between Colorado’s Avery Brewing and California’s Russian River Brewing, is often cited as the beginning of collaboration products.

“It’s the joy of going through your creative paces. It’s like musicians who get together to jam.”—Kevin Martin, Cascade Brewing

Beer lends itself most easily to these partnerships, because production is often quicker, as most beer styles usually don’t require the same aging that spirits and wine do (which can delay bringing the final product to market), and production amounts can more easily be adjusted depending on need. Note, too, that many of these collaborations are one-offs, made for a specific occasion or event, and usually aren’t put into regular production.

“At the core, it’s about building camaraderie and the sharing of ideas,” says Kevin Martin, lead blender at Cascade Brewing in Portland, Ore., which focuses on one major collaboration per year. In 2017, it worked with Bruery Terreux in Anaheim, Calif., to make One Way or Another, a sour ale blend featuring Oregon marionberries and California Meyer lemons. This year, it will collaborate with Upland Brewery in Bloomington, Ind., on a sour ale, called Pearawsterous, using Oregon pears and Indiana paw paw fruit (which has a flavor profile somewhere between a mango and a banana).

“It’s about brewing and blending,” says Martin. “It’s the joy of going through your creative paces. It’s like musicians from different bands who get together to jam.”

Sometimes, product collaborations are part of the producers’ marketing efforts. These, on their own, can be highly successful, say company officials who use them for publicity. Watkins calls it “small business synergy,” where the loyal customers of one brand—and craft customers are notoriously loyal—are introduced to another product, with its own very loyal customers. It’s cross promotion, he says, of the most efficient kind.

But sometimes, reasons crop up where publicity is the last consideration. A few recent examples include:

- After the hurricanes and wildfires last fall, collaboration products were made across the country to raise money for disaster victims. In Florida, officials from Coppertail Brewing in Tampa, Green Bench and Cycle Brewing in St. Petersburg, and 7venth Sun Brewing in Dunedin collaborated on an IPA called, appropriately enough, Irma—complete with donations from suppliers that included hops, malt, and cans.

- Wineries in California regularly donate collaboration barrels to local charity auctions, like last spring’s 10-case special lot, a Pinot Noir blend from 11 producers in the Petaluma Gap Winegrowers Alliance for the 2017 Sonoma County barrel auction.

- Another annual fundraiser is Minneapolis’ In Cahoots!, where 14 local craft producers pair up to make one-off items that are sold the day of the event; each partnership chooses a local charity to benefit. Sociable has participated for four years, in 2017 teaming with Bauhaus Brew Labs to make a pilsner-style lager using apples.

“It’s about giving back to the community,” says Jeffrey Dickinson, cofounder and head distiller at Bear Creek Distillery in Denver, Colo., which is working with State 38 Distilling, Woody Creek Distillers, and Wood’s High Mountain Distillery in the Colorado Whiskey Collaboration. The brainchild of Sean Smiley, who owns State 38, the project’s goal is to produce two barrels of rye after a couple of years of aging, with proceeds donated to a charity chosen by each distillery. It’s similar to other craft whiskey efforts, including the Four Kings series of collaboration whiskeys made by distillers in the Midwest and upper south. “Seeing breweries in the area collaborating with each other and creating really good joint effort projects sparked the idea for us, as distillers, to come together and create a unique whiskey product,” says Dickinson. “As a bonus, we’re able to give back to our local communities. I think that’s what makes this project so neat.”

“You need to plan ahead, and you need to know what the potential problems are about.” —Julia Herz, Brewers Association

Making it work

Not as easy, says Herz, is understanding how to be successful. “You need to be aware of the pitfalls,” she cautions, explaining that the regulatory side can be daunting. “You need to plan ahead, and you need to know what the potential problems are about.”

8th Wonder Brewery in Houston, Texas, joined three other craft producers to create Reunion Ale 2017 in support of an annual event that started in 2010 as a cancer benefit by Shmaltz Brewing in upstate New York. In 2017, proceeds from the four-brewery effort—Shmaltz, 8th Wonder, Renegade Brewing in Denver, Colo., and Terrapin Beer in Athens, Ga.—went to Hurricane Harvey relief. Each participant made its version of a brown ale, working from the same base recipe, and the four brews were released simultaneously at the Great American Beer Festival last fall. “When they asked us to participate, it was a no-brainer,” says Ryan Soroka, the president and co-founder of 8th Wonder.

But getting to the product release is complex, something that’s true for even the simplest collaboration. In this, the Reunion Ale project demonstrates much that collaborators need to know. It features four companies in different parts of the country that use slightly different approaches; in one respect, the only thing the Reunion Ale collaborators have in common is that someone at each brewery used to work or intern for Shmaltz. The 8th Wonder ale, a tongue-in-cheek nod to NEIPAs, was a murky brown IPA named Dirty Coast (in honor of its Houston/Gulf Coast origins). On the other hand, Renegade’s effort, using Colorado-grown Zoso hops, had an almost banana finish. In other words, the same beginning, but decidedly different results.

“There were conference calls, emails, and a lot of talking back and forth,” says Soroka. “Everyone had ideas about what they wanted to do, and we wanted to be sure everyone was on the same page.”

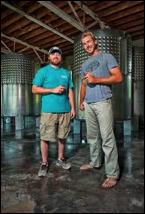

[Photo courtesy Sociable Cider]

A solid and successful collaboration, say those who’ve done it, is centered around three key areas.

First, understand the legal requirements, which are as complicated and potentially cumbersome as anyone who works with alcohol can imagine: Whose license will be used to manufacture the product? If your products are different, like beer and cider, is there a way to reconcile the license requirements? If you’re in different states, do the various laws require each company to manufacture the product in its own facility, as opposed to one company making the base and sharing it with the others? Or does the product need to be started by one collaborator and finished by another? This may be the case if different types of beverage producers work together (a distillery with a brewery or cidery, for example).

Second, make sure everyone understands the collaborative process, which isn’t always as straightforward as it might seem. The four participants in the Colorado whiskey project, for example, had to decide not only on what kind of mash to use, but if each should use the same mash or instead personalize it (in much the same way many craft beer collaborations work). Even then, says Dickinson, three used 100 percent rye in the mash, while a fourth used a 75 percent rye mash. These things happen, laughs Watkins, “It’s a free-wheeling business.”

Third, make sure the collaboration works for the bottom line, even if the product’s goal is not for profit. Martin ticks off all of decisions to be made: How much product to make, what to charge, and what bottle format to use. Other details include, how to distribute the product—at an event, at your facility, through distribution to on- and off-premise accounts, or through some combination of all of these options? How much will each collaborator get to sell? And, if applicable, how much of the proceeds will be donated to charity?

“If you don’t figure all that out early on,” says Martin, “you don’t know that the collaboration will happen. Those factors all have to make financial and promotional sense.”

[Photo courtesy Bear Creek Distillery]

Product collaborations invariably sell out quickly. “I wish we had some more to keep selling,” Soroka says of his Reunion project IPA; company officials report customers regularly ask when they’re going to do another collaboration.

“One of the best parts about what we did was tasting the other beers at the Great American Beer Festival,” says Soroka. “You’re making new friends, and that’s the fun part. They’ll ask you why you did what you did, and you’ll ask them why they did what they did, and what if they had done something differently, or you had done something differently. Collaborations are fun.”

“That’s one of the things about craft brewers,” says Herz. “Everyone understands about working together.” And what’s better than doing good, making a profit, and having fun, too?