Traditionally, brown spirits maturation takes place over many years, mainly in oak barrels or casks carefully nestled in large rickhouses, following the centuries-old formula: alcohol + oak + time = deliciousness.

Traditionally, brown spirits maturation takes place over many years, mainly in oak barrels or casks carefully nestled in large rickhouses, following the centuries-old formula: alcohol + oak + time = deliciousness.

Within the past decade, though, an increasing number of craft distillers have started to look for alternate (read: faster) maturation processes. In doing so, they appear unaware that major bourbon and Scotch whisky producers have been experimenting with acceleration methods for more than 80 years but have declined to adopt rapid maturation for their own purposes. The simple reason may be that maturation is such a vast and complex process that no one understands it completely—maybe no one ever will.

If a distiller’s goal is to produce, via modern processing technologies, a tasty new product that’s acceptable to consumers, with many of the required attributes present in a reasonable harmony, then there’s nothing wrong with seeking a faster approach. To say they’ve reproduced a fully authentic and identical tasting product to one matured over an extended aging period, however, is a completely different story.

Not really new

Not really new

Craft distillers have touted many alternate systems and schemes in an effort to produce quality matured spirits in a fraction of the time it traditionally takes. But, in many cases, they’ve only reintroduced us to their “alternate” methods, many of which were actually put to the test by major distillers many years ago.

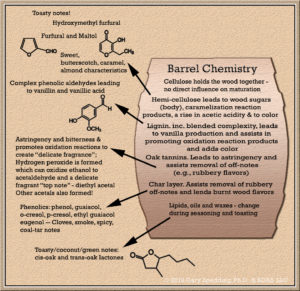

Some distillers’ “outside the barrel” methods involve oak chips, oak spirals, or wood staves (oak and other wood species); or adding tannic substances or increased amounts of ethyl acetate (a key player during spirits maturation) in an effort to mature spirits more rapidly. To be sure of success in this arena, distillers need to understand the effects of oak and other wood on the maturation of alcoholic beverages.

There’s a notable lack of clarity in this area, and many distillers make the mistake of assuming that traditional spirits production methods—with just the added twist of applying an exotic, radical, or eccentric maturation process—will work. But extensive tests for all the flavor molecules produced in a system are meaningless without understanding the actual contribution of those chemical components to the product’s overall flavor profile.

Success is measured by sensory perceptions, with human senses being the final arbiter. However, the tools to evaluate sensory data aren’t yet widely understood. So though some may have even been successful in their efforts, to some degree, further work is needed to determine if they’ve achieved products of comparable quality to those made the traditional way.

A complex formula

Wood is an incredibly complex biological matrix. In addition, the raw spirit itself and the ethanol-water solvent system are also more complex than they may appear at first. Put the units together and the system becomes incredibly more than the sum of its parts.

The time required for satisfactory maturation varies according to the characteristics of the raw distillate (the newly made spirit entering the barrel or aging system); the size, wood origins, and treatments of the cask or barrel; and the environment in which the spirit is matured. The flavor changes of maturing spirits are caused by various influencing factors but can be summed up as follows:

- Direct extraction of wood compounds (naturally lower molecular weight components);

- Decomposition of the many types of wood macromolecules and extraction of their products into the distillate;

- Reactions between wood components and the constituents of the raw distillate;

- Reactions involving only wood extractives;

- Reactions involving only the distillate components; and

- Evaporation of volatile compounds (low boiling point compounds through the wood of the cask).

Without the presence of many of the components derived from wood, aging distillates in non-wood vessels is next to impossible, and it’s doubtful that the full complexity of cask or barrel aging can be achieved or reproduced in vessels containing only wood chips, staves, spirals, or other artificial means of adding such desired constituents.

The effects of seasoning, toasting, and charring wood must also be fully understood before oak chips, staves, or other wood-based additives can suitably mimic the qualities of the oak-barrel wood-engine. When using chips instead of barrels, it’s key to understand that kiln-drying wood arrests development of flavor compounds, whereas natural air seasoning lets them develop. Oven kilning has been used to speed up the process, but it doesn’t add the same level of chemical complexity to the wood. Details on heating oak fragments, or charring them, for use in modern maturation processes are important to understanding the process of alternate maturation.

The effects of seasoning, toasting, and charring wood must also be fully understood before oak chips, staves, or other wood-based additives can suitably mimic the qualities of the oak-barrel wood-engine. When using chips instead of barrels, it’s key to understand that kiln-drying wood arrests development of flavor compounds, whereas natural air seasoning lets them develop. Oven kilning has been used to speed up the process, but it doesn’t add the same level of chemical complexity to the wood. Details on heating oak fragments, or charring them, for use in modern maturation processes are important to understanding the process of alternate maturation.

Oxidation reactions

Micro-oxygenation—the deliberate and carefully delivered introduction of set amounts of oxygen to affect oxidation reactions in wine and spirits—is an important process for maturing liquids in wood, because it lets phenolic compounds derived from the wood mingle with the liquid. Tiny amounts of oxygen play a vital role in barrel aging with impacts upon flavor, aroma, and phenolic composition of aging spirts. In barrel aging, oxygen diffuses into the wood from the ambient air surrounding the casks or barrels. The system itself, with certain chemicals derived from wood, acts to control the oxidation so that oxidative spoilage, leading to detrimental flavors, is avoided.

For rapid maturation systems, micro-oxygenation could possibly be used as an alternative to barrel aging when combined with staves, chips, or exogenously added tannins. It will, however, be important to learn how to control such oxygenation for desired levels of oxidation to occur in nontraditional aging systems. Further flavor development depends upon this oxidation chemistry, and slow oxidation seems to be the order of the day.

The Scottish whisky industry has long been looking into rapid maturation of its famed product. One line of investigation dealt with steel tank-aged wines matured with oak chips, shavings, or staves to supply wood characteristics. Scottish distillers questioned the potential extension of such practices to the cask-matured spirit sector. They found there was some potential for use of such wood products, though “certain reactions, influenced by oxygenation over time, don’t occur in these systems.”

A senior scientist with the Scotch Whisky Research Institute noted that, “if you were trying to achieve similar maturation as that given to Scotch whisky by cask maturation, one of the problems would be that Scotch is traditionally matured in used wood, so getting the right kinds of chips to achieve a similar profile would be difficult.”

Wait and see

Extensive chemistry takes place during the maturation phase of brown spirits, and it’s these reactions that produce the hundreds of compounds that impact the final flavor profile and quality. Many variables are at play and, until the production of all these compounds are understood at a level far beyond where we are now, the rapid maturists will have much work to achieve their desired goals. That said, some alternatives do exist for craft distillers to produce flavorful spirits that might sell well to consumers eager to try new products. Such products may also set the distiller apart from the major players and earn them financial rewards for their efforts in an ever more competitive field.

The research being undertaken today seeks to identify which chemical compounds are the most odor-active contributors to estery and mature/woody-aged characters in malt whisky, tequila, and bourbon, and further, to clarify the flavor interactions between these characters in each of the spirits. Current studies are aimed at developing knowledge of the sensory and/or physicochemical interactions between aroma compounds in various spirit systems and unraveling the resultant effects on flavor perception.

The definitive proof for rapid-maturation seekers will be in satisfying a true authentic taste evaluation by highly trained sensory experts (those that can truly distinguish new from old)—or mass consumer acceptance.

New products may emerge from rapid maturation engines and processes with unique flavor profiles that stand up as alternatives to traditionally matured products, but they may never actually fully compete with them for authentic flavor profiles and overall quality. The cask may yet reign supreme. Only time (a lot of it) will tell.

This article represents a significantly trimmed down and selective summary of a lengthy treatise written by the author. Further details including a complete set of references covering the topic are available upon request at gspedding@alcbevtesting.com.