“Art comes into play with how I blend a variety of ingredients for each vintage and brew. But for quality’s sake, being able to repeat every step in the process is essential.” —Mike Faul, Rabbit’s Foot Meadery

Nearly a quarter-century ago, Mike Faul, a systems engineer turned entrepreneur, founded Rabbit’s Foot Meadery in the heart of California’s Silicon Valley. An early internet pioneer, Faul is no stranger to robust growth—but even he’s surprised by demand for the grog he’s brewed from his Red Branch Cider and Brewing Company since the turn of the century.

“We produced 400 gallons from a two-car garage in 1995,” he says. “Today, we’re bottling 60,000 gallons of mead, cyser, and braggot annually from a 5,000-square-foot warehouse in Sunnyvale [California].”

Faul makes mead, the world’s oldest alcoholic beverage, with traditional recipes and Information Age technology. And, like a handful of mead makers worldwide, he’s coaxing the craft beverage industry into the 21st century. “How much technology do we need to make our products efficiently without sacrificing quality?” he asks.

Brewed from fermenting honey and water, mead predates wine and beer by thousands of years. Like chardonnay or pinot noir winegrapes, honey infuses mead with the aromas and flavors unique to its variety and terroir. Mead can evoke clover, orange blossom, heather, or wildflower notes, for example, depending on the nectar that the bees gather to make honey.

Brewed from fermenting honey and water, mead predates wine and beer by thousands of years. Like chardonnay or pinot noir winegrapes, honey infuses mead with the aromas and flavors unique to its variety and terroir. Mead can evoke clover, orange blossom, heather, or wildflower notes, for example, depending on the nectar that the bees gather to make honey.

Red Branch Cyser is a blend of apple juice, honey, water, and yeast. The recipe calls for 50 percent apple juice and 50 percent honey and water by volume. Variety and terroir matter for cyser, too, and like traditional mead, the brew master can add flavors such as apricot, black cherry, lemon, peach, and raspberry during or after fermentation. Faul also brews braggot, a style of beer made by adding honey to the wort instead of the full amount of malted barley.

“It’s an art and a science,” he admits. “Art comes into play with how I blend a variety of ingredients for each vintage and brew. But for quality’s sake, being able to repeat every step in the process is essential.”

In 2009, Mike Faul leased-to-own a Bared B2 crossflow filtration system.

Programming the remote

Though a traditionalist at heart, Faul has added technology to the mix to refine the way he brews cyser and mead. He mixes honey, yeast, and water or apple juice, then ferments, filters, and pumps it into a conditioning or storage tank before sending it to the bottling line.

“When we leased a filtration system in 2009,” he says, “Red Branch became one of the first cider companies in the United States to use crossflow technology.”

Leased-to-own from an Italian company, the Bared B2 crossflow filter strips spent yeast from the mead or cyser must. Faul connects the filter to the inlet pipe from a fermentation tank and the outlet pipe to a conditioning or storage tank. On cue, a third pipe recirculates through the membrane filter and then to the fermentation tank.

“We run the must through a screen to catch debris and then pump it through the crossflow filter,” he explains. “A pressure transducer monitors the system and ensures that the mead or cyser is flowing through the membrane filter at the correct pressure. As the pressure drops, it flushes filtrate back through the crossflow filter, dislodging the yeast.”

The crossflow filter runs each batch continuously and filters mead and cyser to 0.20 microns—fine enough to remove yeast, haze, and colloids from the fermentation in a single pass. It pumps the filtrate into a tank for carbonating, blending, or storing. As a final step before bottling, the filtrate passes through a sterile filter to ensure the cyser or mead is free of contaminants.

True to his roots, Faul has harnessed the crossflow filter to the production line. “I built a PLC [programmable logic controller] so I can share instructions between the crossflow filter and the fermentation, conditioning, and holding tanks,” he says. “It’s fully automated. I can control the entire process remotely with commands from my cell phone.”

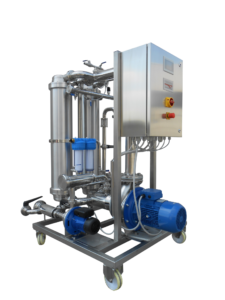

Criveller offers a complete line of automatic and semi-automatic crossflow systems, with either polypropylene (PP) or polyethersulfone (PES) membranes, depending on the product to be filtered. These hollow-fibre polymer membranes are highly resistant to chemicals and heat, making them an excellent solution for filtering still or sparkling wine and cider. [Photo courtesy Criveller Group]

This simple but powerful design can help beverage makers develop a comprehensive vision for how to operate their breweries, cideries, and wineries more productively. The technology Faul has integrated into fermenting and filtering cyser and mead lets him work more efficiently, saving him product and reducing the cost of filtration and labor.

Before he purchased the Bared filter, he compared the cost of filtering mead and cyser with a crossflow filter to the plate-and-frame filter he used during the company’s first 14 years.

“I calculated that the crossflow filter would pay for itself in a year-and-a-half,” he says. “Considering product loss, the cost of plate-and-frame filters, and labor, I could save up to $2,750 per batch.”

With the plate-and-frame filter, he lost more than 150 gallons of mead from each 2,000 gallon batch. Today, the crossflow filter leaves a 35-gallon slurry of yeast behind.

“Membrane filters can last decades,” he says. “I’ve run my crossflow filter for 10 years at 60,000 gallons per year. That’s 600,000 gallons of product without replacing the filter. A plate-and-frame set-up requires a new set of filters every 250 gallons of product that has yeast in suspension.”

Another advantage to crossflow, says Faul, is its ease of operation. “We’ve increased production dramatically over the years, but with added technology we’ve kept the same number of employees,” he says. “The crossflow filter shuts off automatically. So I can run a batch overnight without hiring a technician to watch over the filtration.”

TMCI Padovan’s DYNAMOS High Solids Dynamic Cross Flow system: This patented, high-solids filter features rotating ceramic disc membranes and a calibrated back-pulse system. It allows filtering not only of juice lees, but also wine lees, with optimal results, even better than the ones obtained with tubular style high solids filters. [Photo courtesy ATP Group]

In a side-by-side comparison between crossflow and plate-and-frame filtration, Faul saved $1,837 worth of product, $548 for pad filters, and $360 in labor per 2,000-gallon batch when he chose crossflow over plate-and-frame filtration.

Other Voices

The craft beverage industry is advancing the technology along many fronts. Scientists and engineers at the Criveller Group, the ATP Group, and the Della Toffola Group, for example, are exploring ways to perfect crossflow filtration.

Engineers at California-based Criveller have designed and added a variable flow pump to their crossflow filtration system. “Our crossflow filter pump starts out gently,” says Davide Criveller, enologist for the Criveller Group. “With no drop in pressure, a PLC increases the flow rate, regulating transmembrane pressure to increase overall recovery rate, reduce clogging, and extend the life of the membrane.”

Omnia 170 High Solids Ceramic Membrane Crossflow Filter: The OMNIA filters are suitable

for filtering products of all kinds, however dirty, obtaining the best clarity and retrieving as much product as possible. [Photo courtesy Della Toffola]

With crossflow filtration so popular, engineers at Della Toffola have developed a crossflow filter with ceramic membranes with a titanium oxide coating that eliminates carryover of color and flavor from filtering beer, cider, mead, or wine.

With so much to gain, brew masters like Faul are adopting crossflow filtration at an accelerating pace. The number of crossflow filters in use at U.S. meaderys, for example, could double next year.

“Mike Faul, along with four or five other meadmakers, are drawing on their experiences and perspectives to raise the quality of beverages made from fruit, grains, and honey by an order of magnitude,” says Dr. David Block, chairman of the department of viticulture and enology at U.C. Davis. “He’s at the forefront of developing innovative products with leading-edge technology.”

With 500 licensed meaderys operating in the United States and products made with apples, berries, citrus, exotic fruit, grapes, pears, spices, or stone fruit and wine yeast, brettanomyces, or lactobacillus, the craft is ripe for yielding beverages that could expand today’s markets and someday create markets of their own.