In 2009, when J.J. Williams joined Kiona Vineyards, his family’s business in Benton City, Wash., he brought with him a few new ideas. These included a new emphasis on branding, separate marketing plans for the winery’s three-tier distribution and direct-to-consumer products, and reduced production to increase profit margins. He also wrote a corporate mission statement: “We want to be around and owned by the Williams family 100 years from now.”

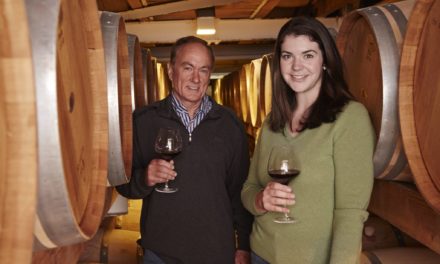

Three generations of the Williams family (left to right): John, Scott, and J.J. [Photo courtesy Kiona Vineyards]

Williams certainly didn’t invent the idea of family longevity. His grandparents, John and Ann Williams, started the company in 1975, when they planted the first grapes on Washington’s famed Red Mountain. His father, Scott, has been running the company since the early 1980s. Kiona Vineyards has grown because John encouraged and empowered the next two generations of the Williams family to run the business. But J.J.’s mission statement puts the founders’ commitment into words and sets up Kiona for a smooth succession for generations to come.

It’s the kind of thinking legal and financial advisors like to see, particularly in the beverage industry, where tightly held companies dominate, and where regulations and tax structures that vary across 50 states can play havoc with producers’ survival rates from one generation to the next. Experts agree that strong corporate documents, ones that clearly define a company’s structure, along with regular reviews of a company’s—and the next generation’s—strengths and weaknesses, can help set the groundwork for succession.

Early planning is key

Kevin E. Regan and Tyler Jones, attorneys with Seattle law firm Helsell Fetterman LLP, work with many clients in the beverage industry, including wineries, breweries, cideries, and distilleries. “Statistically, around half of family-owned businesses fail when transitioning from generation one to generation two,” says Jones. Often, a winery or brewery is owned and operated by someone who’s already had a successful career in another field and is pouring passion—and money—into his or her new venture.

“Statistically, around half of family-owned businesses fail when transitioning from generation one to generation two.” —Tyler Jones, Helsell Fetterman LLP

“In my experience, most people are very good at running their business. In the earliest phases, they’re really focused on getting their product out the door,” says Regan. “They’re 100 percent gung-ho on growing their brand and their presence in the marketplace.” These entrepreneurs might also have a strong vision of the future, one that often includes their children. Planning for that future, Regan and Jones say, is as important as crushing the grapes or distilling the mash. That plan can succeed or fail based on how the company’s building blocks are structured from the beginning.

“Maybe the family patriarch wants to start bringing his children into [the business],” Jones says. “He thinks that, because the family has a crystal clear image of this succession plan, it will just happen.” Good corporate documentation, besides helping a business run smoothly, also helps build a smooth succession plan. Regan says, “An estate plan is a must for any business owner who envisions it going to the next generation.”

That’s partially because the beverage industry is so highly regulated. Corporate governance, such as a buy-sell policy, is one of the first ways to assure a good succession when a founder retires or passes away. Those day-to-day business concerns can also affect succession, and these issues grow as the company grows, say Regan: “There are business continuity concerns about things such as purchase contracts for grapes or distribution agreements, which often have provisions that limit the ability of a producer to transfer their interests in the business. You want to make sure that distribution agreements allow for a transition in a way that’s meaningful.”

“An estate plan is a must for any business owner who envisions it going to the next generation.” —Kevin E. Regan, Helsell Fetterman

Honestly evaluate all options

Jay Silverstein, a partner with the Seattle, Wash.-based accounting firm Moss Adams (he’s located in the firm’s Santa Rosa, Calif. office), advises clients on succession planning and other matters. He has the most success, he says, with clients who start the wheels of their succession plan rolling 10 to 15 years before their own departure from the business.

“Sometimes a meaningful strategy takes time to implement,” he explains. “There are a number of elements in the basket, including how to help the kids grow into the role of business owners, but also helping to extricate the current owners from controlling the business.”

Silverstein identifies a few key parts of a strong succession plan, including the personal financial needs of the current owners. Some have amassed wealth outside their beverage company, but others rely on cash flow from the business for living expenses. If the winery or distillery doesn’t generate enough income, it might become necessary to sell the business rather than passing it on to the next generation.

Silverstein also advises considering how well the business is currently operating. Wineries are often land-rich, cash-poor operations, making them difficult to divide among multiple heirs. In addition, onerous estate taxes might force successors to sell the company. A business owner can ease those problems by gifting portions of the company to the next generation over a period of time. Another tactic might be to separate real estate assets (vineyards) from operating assets (a production facility).

The current owner’s estate planning goals and objectives should always be a priority. A brewery owner might envision her children operating the business long after she’s gone, keeping alive the family legacy. But that vision can become complicated if the founder relies on the business for retirement income or if she wants to divide the assets equally between multiple offspring. With early planning, a business owner can also take steps to minimize estate taxes, an important consideration in states such as Washington, where estates are taxed at $5 million, a much lower threshold than the new $20 million federal level.

Finally, Silverstein advises, remember that not all heirs are created equal. Maybe the founders envision their daughter taking over as CEO while their son shoulders the winemaking duties. It’s not uncommon to find that neither heir is particularly well suited for—or interested in—those roles. Or older siblings might have more experience or more interest in the company than younger children when the parents exit.

Silverstein’s office offers an evaluation service that involves interviewing all potential successors—offspring, other relatives, and key employees—along with the founders, about expectations and skills. He recalls one case where, out of five potential people who could have taken over as CEO, the client’s two children were rated fourth and fifth. In cases like that, he says, the succession plan might include a bridge period, when a competent CEO manages the company until heirs, who retain ownership, are prepared to step in.

“As a result of the tax law changes, revisiting entity structure can be beneficial.” —Evelyn Cook, Cook CPA Group

Costs and related concerns

Several sources interviewed for this story echo the value of formally evaluating corporate strengths and weaknesses, as well as the abilities and interests of the people tagged for possible succession. Evelyn Cook, president of the Cook CPA Group in Roseville, Calif., says it becomes particularly important when intangible assets lie with an employee and not a family member. “If you have a great winemaker who’s developed a great label, that might correlate with more sales or let you sell your product at more per case, and that’s going to increase your value.” In that case, she says, an owner might want to build in incentives, through bonuses or an ownership plan, to keep that employee involved.

Depending on the size of the company, Cook says, such an evaluation can cost anywhere from $7,000 to $20,000. “But it’s a good first step for someone who’s planning to exit the business in the next five to seven years. It’s a good measuring tool. With the price of land being so high in California, and the value of equipment, it’s important to figure out ways to determine what family members are going to be involved and, specifically, how they’ll be involved.”

Cook also recommends a regular review of a company’s documents and governance, with an eye to problems the next generation will face. For example, it’s still common for a winery or brewery to operate as an LLC, she says, but it might make sense to convert to a C corporation, especially if retiring owners have another source of income. “As a result of the tax law changes, revisiting entity structure can be beneficial,” says Cook. As a C corp, a winery’s income in 2018 will be taxed at 21 percent. If the income passes through directly to owners, they might be bumped instead into the highest personal tax rate.

“People often look at succession as if it’s a single event, that one day dad is going to hand over the keys and walk away. … but [it’s] an evolving partnership,” —Dennis Jaffe, Ph.D.

“The truth is, it’s not about simple succession but about an evolving partnership. It starts out when the kids are young and inexperienced and they love their father and listen to everything he says. Then it begins to shift. The kids take on more and more responsibility and the father pulls back and becomes less involved. It’s as much as a 20-year process, really, a role shift.” Often, Jaffe focuses on counseling the older generation to step away, even as early as in their 50s.

Creating a dynasty

Even the best-laid plans can’t prevent every problem. By the time a winery is owned by a fourth or even fifth generation, the number of people involved can directly correlate to the complexity of the transition. But family dynamics, while unpredictable, aren’t insurmountable. “When you see these dynastic families,” Silverstein says, “it’s usually because they’ve done a good job educating their children early on in the transition.”

The Mondavi family of Napa Valley has seen both sides of this issue. When family patriarch Cesare Mondavi bequeathed the company to his two sons, Robert and Peter, the brothers couldn’t agree on how to take the company forward. This led to a rift that lasted more than 40 years and resulted in two separate branches of the Mondavi family establishing wine dynasties. After the split, Peter Mondavi, Sr., continued to lead C. Mondavi & Family, eventually running the company with his sons, Marc and Peter Mondavi, Jr. Today, C. Mondavi & Family, founded in the 1940s by Cesare and Rosa Mondavi, is welcoming the fourth generation (G4) of Mondavis to the family business as major shareholders and brand ambassadors. Several also hold management positions with the company or sit on the board of directors. Marc and Peter Jr., are still in charge but are preparing their children to take over the family business in the years to come.

“I can say for all of us in this next generation, we’re extremely humbled to carry on a wine legacy started by our great grandparents.” —Riana Mondavi, C. Mondavi & Family

“At C. Mondavi & Family, we’ve made a commitment to continue family ownership and traditions,” says G4 family member, Riana Mondavi. “Passion has kept our family business going this long and I can say for all of us in this next generation, we are extremely humbled to carry on a wine legacy started by our great grandparents.”

For the Williams family, building the business has been a decades-long venture. John and his wife Ann invested heavily to launch Kiona, and John maintained his career as a metallurgist during its growth. Their four children, including Scott, maintain ownership now. Grandson J.J. felt the family passion even before he started working on the farm as a teenager. He’s looking forward to his brother, Tyler, who’s spent the last 10 years working in Washington state and internationally as a winemaker, joining him in the cellar. And, J.J. adds, if his own two children are interested, he hopes to be able to bring them into the business someday as well.

Planning can help make it happen. Attorney Jones of Helsell Fetterman recalls one client who started a small winery in Washington state and successfully passed the business on to his daughter, who took the business to the next level. “Now the dad doesn’t have to work every day,” Jones says. “He just shows up and drinks his wine. It’s a beautiful thing.”