Selling wines made from an unfamiliar grape isn’t easy. But when successful, the efforts can pay huge dividends for vintners and growers passionate enough to take the risks. The latest case in point is Tannat, a variety known for its dark color, juicy flavors, vibrant acidity, and chewy tannins. I’ll never forget the first time I tasted this intriguing grape variety, nearly 15 years ago in the underground wine cave at Tablas Creek Winery in Paso Robles, Calif., where winemaker Neil Collins had just started tinkering with it.

“[Tannat] was like nothing I’d ever worked with before.” —Neil Collins, Tablas Creek Winery

“To me, it was a whole new experience,” he says. “With a combination of power, finesse, and a dark inky hue, I’ll never forget how the fragrant aromas would lead to an incredible burst of big, ripe flavors on the mid-palate and the hallmark tannins at the end. It was like nothing I’d ever worked with before.”

In 2002, in response to a petition from Tablas Creek, the Bureau of Alcohol and Firearms (BATF) added Tannat to the list of grapes that can be designated on wine labels (either in single varietal wines or blends). In doing so, BATF opened up the gates for what’s since become a few hundred acres of this hearty grape variety in California, Oregon, Arizona, Texas, Virginia, and Maryland.

In addition to grapes with thick skins, distinctive flavors, high levels of acidity, and an ample helping of tannins, Tannat vines are naturally rugged, resilient, and relatively easy to grow. They’re resistant to frost, love heat, and hold up well under drought conditions.

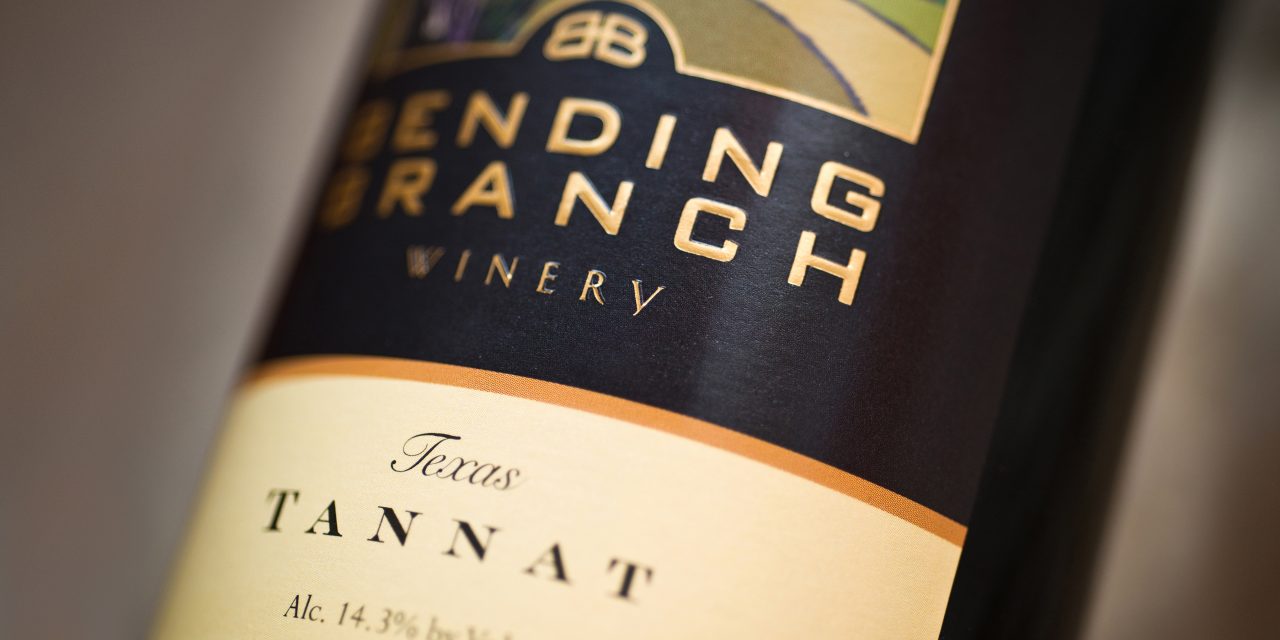

In Texas, these benefits have resulted in Tannat being planted in more than 20 vineyards over the past decade. One advocate of the variety is Robert W. Young, M.D., proprietor of Bending Branch Winery. Young fell in love with the Texas Hill Country winegrowing region while visiting his daughter, who moved to the area in the mid 2000s. After enrolling in the winemaking certification program at UC Davis, he met veteran winemaker Greg Stokes, who’d been working with Tannat at his Placerville, Calif.-based winery, Ursa Vineyards, over the previous decade.

“The success of our Texas Tannat has helped spread the words about the grape to a growing number of sommeliers, wine educators, and wine enthusiasts.” —Robert Young, Bending Branch Winery

While developing (with Stokes’ help) what’s now five acres of Tannat at his family’s vineyard near Comfort, Tex., in 2009, Young released his first Bending Branch Tannat using fruit from the Bella Collina Vineyard in Paso Robles. Two years later, the wine won a gold medal and the prestigious Grand Star Award for best in show at the Lone Star International Wine Competition.

Today, Bending Branch features vineyard designate Tannat offerings from Paso Robles and the Silvaspoons Vineyard in Lodi, Calif., as well as its annual release of Texas Tannat, made with fruit from the Texas High Plains AVA and other nearby vineyards. “The success of our Texas Tannat has helped spread the word about the grape to a growing number of sommeliers, wine educators, and wine enthusiasts in Austin, San Antonio, and beyond,” says Jennifer McInnis Fadel, general manager of Bending Branch, whose marketing program includes the catchy slogan “Tannat Tonight, Honey.”

About Tannat

Many pioneers willing to work with this relatively unknown grape in the U.S. market were inspired by the robust tannin-driven wines worth cellaring from the historic Madiran region and other warm winegrowing areas in the Basque region of southwest France. Others were motivated by the impressive stream of highly touted Tannat-based wines, originating in the cooler winegrowing regions of Uruguay, that hit the United States in the 1990s.

In Uruguay, the first Tannat vines were planted by Basque immigrant Pascal Harriague, near the inland area city of Salto, in 1870. Today, according to international outreach organization Wines of Uruguay, Tannat now represents one-third of all the wines produced in that country, and the highest concentration of Tannat vineyards are planted near the coastal areas in the southern half of the country.

“We want to put Tannat on the world map.” —Christian Wylie, Bodega Garzon

One winery committed to working with this unique grape is Bodega Garzon in the foothills west of the popular coastal destinations of Punta del Este and Jose Ignacio. The expansive vineyards cover 217 hectares with a mixture of white and red varietals; at only 11 miles from the Atlantic Ocean, the estate’s 65 hectares of Tannat vines are divided into a matrix of small blocks and different hillside facings—each influenced by diverse microclimates and well-drained soils (a variation of decomposed granite, basalt and clay). Yields are relatively low, which helps preserve the deep flavors and the expressive notes of mineral, earth, and fresh herbs.

For export, the estate’s flagship is the Tannat Reserva, with fragrant aromas of dried lavender, violet, wild berries, and mineral. On the palate, the wine opens up with tantalizing notes of ripe plum, blackberry, white pepper, balanced tannins, and a long, graceful finish.

“We want to put Tannat on the world map,” says Christian Wylie, general manager of Bodega Garzon. “Beyond its impact on Uruguay, we want wines made with the grape to change the perception of our country and South America as a whole.”

There are now more than 20 Uruguay-based wineries exporting into the United States, meaning there’s a nice selection of Tannat on store shelves and wine lists around the country. Many of these medium- to full-bodied red wines feature fresh flavors of raspberry, blackberry, and other red and black fruits, enhanced with layers of mineral and spice.

“It’s my special ingredient that makes the magnificent flavors in the blend really pop.” —Ben Cane, Westwood Winery

Blends and Rosés

Because of its high level of tannins, many Tannat-based wines are dark, rich, and meaty; key marketplace descriptors include “complex flavors,” “balanced tannins,” “robust” and “bold.” In addition to being bottled as a stand-alone variety, Tannat is also an excellent blending grape. In Madiran, for instance, it’s common to add Cabernet Sauvignon and Cabernet Franc to help soften Tannat’s tannins. In Uruguay, the variety is often blended with Pinot Noir or Merlot to give the finished wine deeper flavors and a stronger backbone.

Variations can also be found stateside. In Sonoma County, Calif., winemaker Ben Cane of Westwood Winery blended 45 percent Tannat (grown at the winery’s Annadel Gap Vineyard) with 44 percent Syrah and 11 percent Counoise to add more floral aromas, complex flavors, and structure to its 2014 Legend red blend. “It’s my special ingredient that makes the magnificent flavors in the blend really pop,” says Cane. The 2015 Legend will include estate Tannat, Syrah, Grenache, Mourvedre, Cabernet Sauvignon, and Counoise, as well as Zinfandel from Dry Creek Valley.

“Tannat wants to be your friend.” William Sherer, Remix Wines

There are also a number of domestic pink wines made with the grape. For his Remix label, Master Sommelier William Sherer makes his Somm Rosé with Tannat fruit he purchases in Lodi, Calif. Thanks to the dark natural hue of the variety, Sherer bypasses the skin-to-juice contact once the grapes are picked, instead going directly to press.

“Tannat wants to be your friend,” says Sherer, who’s also head sommelier at Redd restaurant in Yountville, Calif. “With vibrant notes of plum, mixed berries, and tangy acidity, the colorful fruit lets me make a style of rosé that stands on its own.” He enjoys presenting his wine to consumers as a tasty alternative to popular rosés made with Pinot Noir, Grenache, Syrah, Sangiovese and Bordeaux varietals.

Pairing food with Tannat

When it comes to food and wine pairings, the full-bodied style of Tannat (or blends including it) works well with rich and fatty cuisine, says winemaker Yannick Rousseau of Y. Rousseau Wines in Napa, Calif. Rousseau’s father and grandfather were butchers in the Gascony region of France, and Rousseau is used to eating gamey meats like rabbit, duck, and rich dishes such as cassoulet, paired with Tannat.

“There’s no doubt Tannat can be a beast.” —Yannick Rousseau, Y. Rousseau Wines

While attending wine school in Toulouse, France, Rousseau completed an internship at Chateau Monduse, an iconic winery in the Madiran AOC, where he began working with Tannat grapes in 1997. Today, Rousseau offers three separate bottlings of wines made with Tannat grapes (sourced from California’s Sonoma, Mendocino, and Solano counties).

“There’s no doubt Tannat can be a beast,” says Rousseau, with a grin. “But while it’s always true that it has an ample amount of tannins, it also has acidity. That’s a blessing when it comes to working with complex and well-seasoned dishes.”

Jason Haas, general manager at Tablas Creek, says the winery’s annual Tannat release has a growing following, especially from wine club members and visitors who like big red wines. “Rhone varieties are all about balance, while Tannat is more about power,” he says. “When you add in the herby and tobacco notes it picks up from where it’s planted in our vineyard, suddenly it becomes a wine that can appeal to people who really enjoy drinking Cabernet Sauvignon.”

Rousseau agrees, and is encouraged that Tannat wines are starting to appeal to a wide range of rising star sommeliers, especially those who work with dry-aged beef, gamey meats, or dishes seasoned heavily with salt, pepper, or other spices. “To me, it’s easy to compare Tannat to a mountain Cabernet—a balanced wine packed with fresh flavors, acidity, tannins, and structure,” he says. “It’s a great variety that gives sommeliers an opportunity to add more depth to their wine list.”

The same can be said for adventurous wine drinkers looking to expand their knowledge and please their palates. Because Tannat is rather new and unfamiliar here, it’s imperative for growers and winemakers to educate consumers and hospitality professionals about the wine’s traditional flavor profile, different styles and blends, and food pairing options. By advancing the dialog at every possible opportunity, the grape will move toward the familiar and, if communicated and marketed properly, could become the U.S. wine world’s “next big thing.”