Launching a new beverage alcohol brand in the 21st century is a lot like trying to get your child into an Ivy League school: There are plenty of deserving candidates but only a fraction will find success.

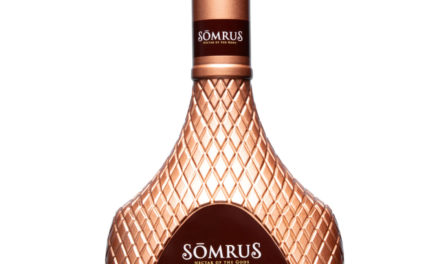

For producers, crafting a quality liquid is only the first step in the long haul to market. As with any other commercial product, the search for a consumer base can be bolstered by packaging, presentation, and marketing. To make an impact on the market, producers frequently seek out firms that provide design and branding expertise for tasks as straightforward as label design and art direction as well as complex needs such as developing product names, back stories, design concepts, visual style, and market appeal. Bottle and closure type, overall imagery and typeface, color cues, paper quality, ancillary packaging and presentations—all this should flow from a comprehensive decision about what the brand is, say designers.

So how does an aspiring brand owner get started finding the appropriate look for their liquid? It’s not just a matter of a few meetings and handing over responsibility to someone else, and producers should be prepared for a tough question.

“You don’t hire Banksy to package Tiffany.” —Kevin Shaw, Stranger & Stranger

“We begin by asking why anyone should care,” says Kevin Shaw, founder of Stranger & Stranger, an award-winning packaging design company specializing in the alcoholic drinks industry based in New York, N.Y., and San Francisco, Calif. “It’s a pretty brutal question and asking people what they stand for can lead down an existential wormhole, but it helps focus everyone on the real issue: the consumer.

“What do we want people to think about your product?” he continues. “Why is it better? Why should they try it? What’s the story? If something about the story turns into a good strategy then it pretty much designs itself. But, more often than not, we keep on until we find something.

“It’s our job to help define where the product sits, profile the consumer, and analyze the competition—and that’s before we even get around to naming the thing, which is a nightmare these days as all the great names have been trademarked.”

More Than Visuals

The need for strong visual appeal explains the frequent redesigns that major brands undergo as trends and fashions evolve. New brands need it even more. Case in point: Before St-Germain (now owned by Bacardi), few spirits evoked the Belle Epoque style that Portland, Ore.-based Sandstrom Partners devised to help make the cocktail-geeky elderflower liqueur a success.

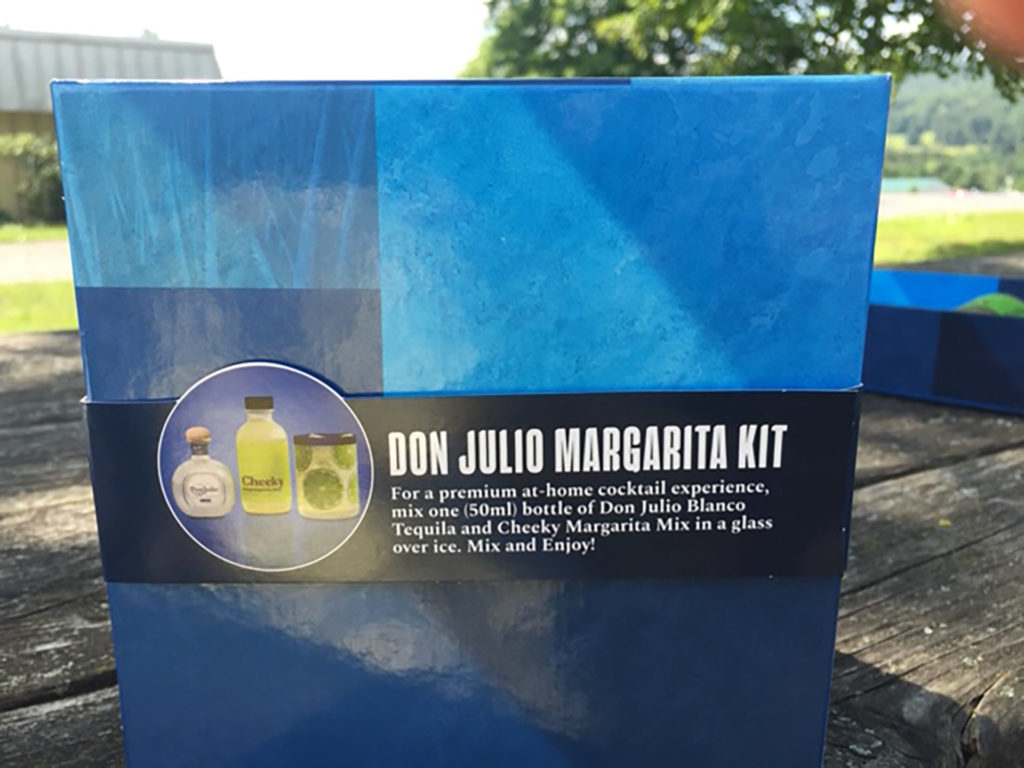

Other firms create similar attention-getting designs. The Rooster Factory, a Pasadena, Calif.-based creative and marketing agency specializing in the drinks industry, has had a hand in brands such as Plantation Rum, Old Duff Genever, and Ferrand Cognac; Stranger & Stranger counts 19 Crimes, Kraken, and Knob Creek among its clients; CF Napa Brand Design (Napa, Calif.) has worked with Concha Y Toro and Mondavi, among others, and The Spearhead Group (Yardley, Penn.) designs and manufactures for Diageo brands including Crown Royal, Don Julio, and Smirnoff.

“It’s important to develop the strategy and story behind the brand and pull those through the design.” —David Schueman, CFNapa

CFNapa owner David Schuemann says that, when launching a brand, many producers don’t fully understand what their design and packaging needs are. “We offer brand strategy as well as design,” he says. “It’s important to develop the strategy and story behind the brand and pull those through the design.”

As he put it in a recent article about design trends, “Memorable packaging reinforces brand name, inspires trial, reinforces the consumer’s enjoyment of the product, and assists recall for repurchase.”

“Design without strategy is decoration,” says Sandstrom President Jack Peterson. “There are a lot of great designers and firms that can do a really good job of creating a competent spirit brand. The problem is, the category has become so overly proliferated that there are thousands of gins, vodkas, and whiskeys. So from a macro view, by definition, that’s a commodity market and the best brand stories win.”

The Work Process

Typically, the process starts with a conversation between a design firm and a beverage producer to focus the work and define expectations. According to Audrey Fort, co-founder of The Rooster Factory, these early creative briefs need to examine a producer’s goals; favored styles, graphics and images; potential market niches; target consumers; cost limitations, distribution channels, and other matters so designers can better understand a product and its positioning.

“When you create a packaging, you want the product’s story to emerge and help people to understand what it is they’re buying,” she says. “Packaging is not art in its own bubble. It has to create or answer a need. We’re here to help sell the product—that’s the ultimate goal.”

There are three general types of producer clients, says Shaw: corporations, former corporate folks with startups, and newbies with no drinks business experience. “The first two generally have historical experience with branding firms or can ask colleagues about their experiences, but for those new to the industry, it must look like a minefield. ”

“Packaging is not art in its own bubble. It has to create or answer a need.” —Audrey Fort, The Rooster Factory

Designers say they must dig deep when a new client has no idea what direction to take, which is where the brief comes in. Alternately, some producers will grant creative freedom, which can cut two ways. “[It] gives us a lot of freedom,” admits Fort, “yet we’ve had unfortunate adventures when a client doesn’t have any clue and doesn’t start thinking [about what they want] until the options are in front of them.”

The proliferation of craft distillers means most firms are handling many new brands. “Since we work with craft distillers, one of the first discussions we typically have is are they going to develop a branded house or a house of brands,” says Schuemann. “It’s a big question when you start: Are you going to have more than one brand or use the distillery name on all your brands?”

Tying together all the pieces of a package design—glass, graphics, label, closure, and extras—can constrain many novice producers, says Lana Toler, marketing and innovation manager for Yardley, Penn.-based The Spearhead Group.

“Often, people will know what box or closure they want, but they don’t have a single point of contact that can supply them [everything]. A client needs to look at the whole picture. A bottle from one source, a closure from another—packaging components need to work together versus being developed in their own silos.”

Sourcing materials

Glass, of course, is a major concern.

“Packaging components need to work together versus being developed in their own silos.” —Lana Toler, The Spearhead Group

Custom bottles are more common these days, and the proliferation of new designs for craft has emboldened many established producers to reconsider their current packages, says Schuemann.

Existing glass vessels are likely to be less expensive and time consuming to source, and can be effective when a designer can take something that exists in the market and improve the equity with an innovative label, closure, or other enhancement, says Toler. “It’s especially useful when a client has low volume and limited in-house resources and wants to get a product to market.”

Bespoke glass is a different story. “We can get labels ready to go in a matter of weeks, and stock bottles are available off the shelf at most glass houses. But creating bespoke bottles involves making molds, producing mockups and test runs, and delivery can take anywhere from six to eight months,” says Shaw, who once saw a tricky bottle project reach the 22-month mark.

Practicalities like these can slow a release down. Who will bottle or can the beverage, and what are the timing deadlines? Are there issues with labeling? “Labels that go over the top of the closure on a bottle tend to be hand applied; this can slow down production and be a hidden cost,” warns Schuemann.

And these days, sustainability is becoming increasingly important, particularly when it comes to gift giving and added value, both of which are growing in importance in the post-COVID-19 era, says The Spearhead Group’s Toler.

Find a Good Fit

When choosing a design firm, Fort advises producers to examine an agency’s previous work to get a sense of its signature and speak with them to see if they are a potential good fit. If a producer is unsure which direction to take, choose a firm that can cover many different approaches.

Get specific about an agency’s work methodology, ask for references about outcome and process, and on budget, timelines, and price changes. “Missed deadlines can be costly,” says Schuemann.

Perhaps most important, decide if there’s a cultural fit. “You don’t hire Banksy to package Tiffany,” says Stranger & Stranger’s Shaw.

Small producers may need an agency that’s skilled in more than branding and illustration, one that can also discuss marketing and brand positioning. And while it may be tempting to go outside beverage alcohol designers, that can cause unexpected problems due to the stringent regulations governing the alcohol industry. Says Shaw, “Packaging toothpaste is a totally different skill set to packaging liquor, and you don’t want a design firm using your brand as a learning curve.”

Packaging success should be measured in sales, he adds, suggesting prospective clients ask to see a firm’s return-on-investment case studies.

In a final word of warning, Shaw cautions falling in love with a design. It’s important to remember that the image you project is meant to attract buyers, he says. “Sometimes with people new to the industry it becomes personal. They have to learn that the consumer is king. Let the designers design. We can get you the first sale, the second is down to your product.”

Make sure your package design moves you to the head of the class.